Corrupting the Classics #4: Revolving Aces

Learn two unique versions of the Herb Zarrow classic called "Albion Aces" and "High Card to Hell"!

Welcome to another edition of Corrupting the Classics, where we explore, reimagine, and breathe new life into time-tested magic tricks—or completely ruin them with “improvements”, depending on your point of view! In this fourth instalment, we’ll explore a real gem of close-up magic that goes by several names, such as “Revolving Aces”, “Emerald Isle Aces”, or simply “The Four-Ace Trick”.

This particular effect has a curious history that includes a surprising case of misattributed credit—a common occurrence in the world of magic. But more on that thorny subject shortly!

In this article, we’ll explore the history and evolution of this effect and present two new approaches that maintain the trick’s core appeal while adding a few contemporary touches. Whether you’re familiar with the original handling or encountering this classic for the first time, I’m sure you’ll find something valuable in these variations.

The Basic Effect

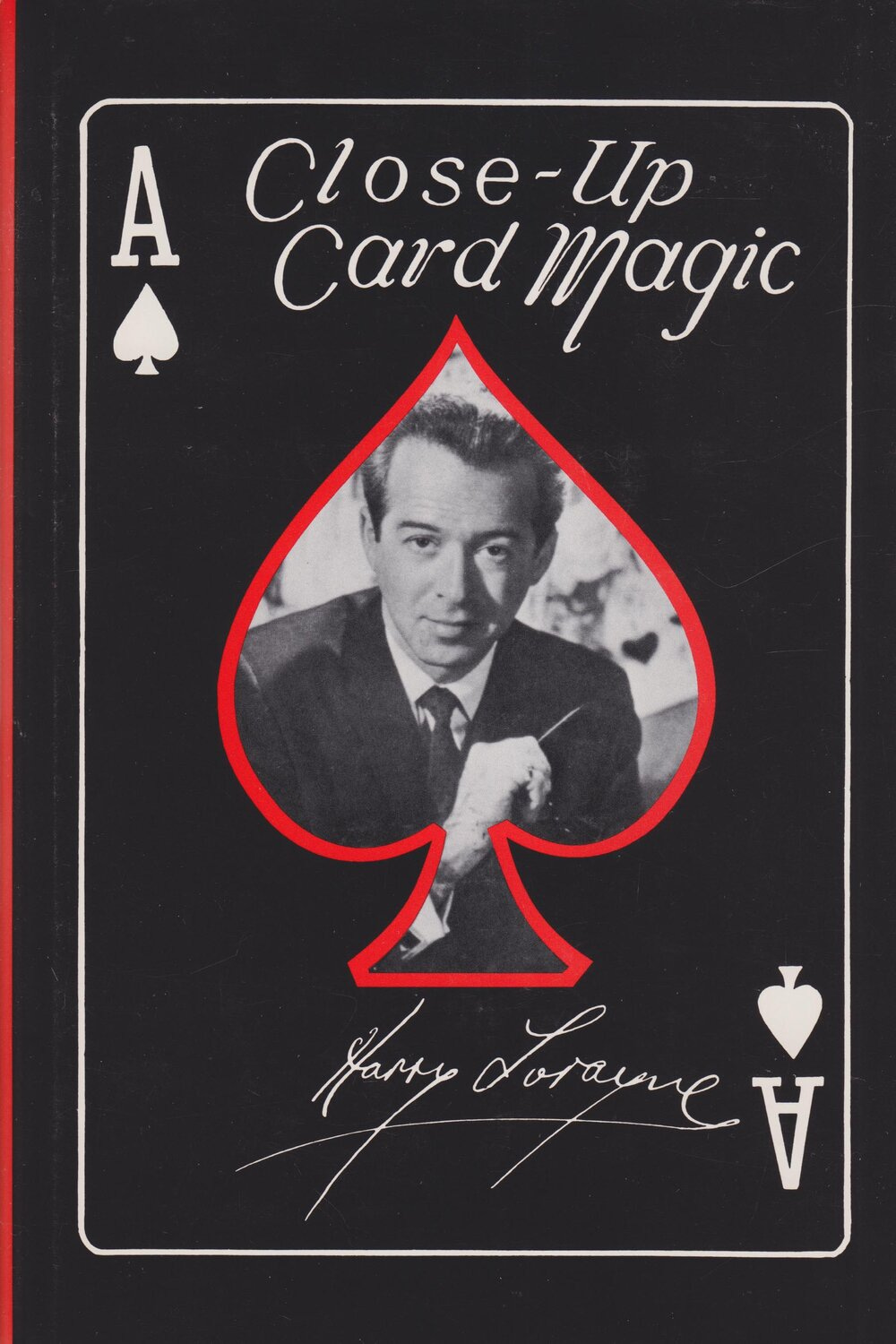

In its classic form, as described by Harry Lorayne in Close-Up Card Magic (1962), the effect is deceptively simple yet highly deceptive! A spectator is asked to stop the magician several times as they riffle through a deck of cards. Each time they stop, a portion of the deck is turned face-up and spread on the table, with a single face-down card placed across it. This process is repeated four times, creating four separate spreads of face-up cards, each with a mysterious face-down card lying across it. When these face-down cards are finally revealed, they prove to be none other than the four Aces! The simplicity and elegance of the method make it a must-learn for any card magic enthusiast.

What makes this trick particularly special is its apparent fairness. The spectator appears to have complete freedom in choosing where to stop the magician, yet the Aces invariably appear at precisely those points. Even more ingeniously, Zarrow suggested performing a genuine demonstration of the stopping procedure before the actual trick begins (forcing an indifferent card on the spectator)—a subtle touch that makes the method even more impenetrable (this is a subtlety that I use in “Albion Aces”—more on this trick in a moment).

History of the Trick

The story of “Revolving Aces” is a fascinating example of how magical effects can sometimes become entangled in accidental attribution controversies. Its origin story is worthy of a detective novel! It first appeared in Genii Magazine (Vol. 25, May 1961, No. 9) as “Emerald Isle Aces”, credited to celebrated Canadian conjurer Dai Vernon.

The following year, it appeared in Harry Lorayne’s Close-Up Card Magic (1962), credited to his “good friend” Herb Zarrow.

The Genii article, written by Hubert Lambert, went to considerable lengths to justify the trick’s name, including a detailed exploration of Vernon’s supposed Irish heritage. (For what it’s worth, I think “Emerald Isle Aces” is a far better title than “Revolving Aces”—a name I consistently misread as “Revolting Aces”!) Lambert even included a photograph of The Professor alongside the explanation, lending the article additional authority. Yet this entire attribution was based on a simple miscommunication between Faucett Ross and Hubert Lambert—an error that would ripple through magic literature for many years.

This misattribution was subsequently perpetuated through several influential publications. Lewis Ganson included the effect in Ultimate Secrets of Card Magic, maintaining the incorrect Vernon credit. The error was further compounded when Glenn Gravatt—somewhat notorious in magic circles for his cavalier approach to crediting—reprinted the trick as “Vernon’s Four-Ace Trick” in his book 50 More Modern Card Tricks (1979).

The mistake was finally corrected when Stephen Minch revealed that Herb Zarrow should rightly receive credit for the trick in The Vernon Chronicles: Further Lost Inner Secrets (1989). The confusion arose from a simple communication error between Ross and Lambert; however, this mistake gained momentum as subsequent authors depended on these earlier erroneous sources.

This misunderstanding led to what may be the most fitting title for the trick, given to it by writer, consultant, and fellow Substack author David Britland. He calls it “The Trick That Wasn’t Vernon’s”! You can see David perform it in the video below. (You can also learn the details of David Britland’s handling in Cardopolis Newsletter #14.)

This case of misattributed credit serves as a reminder of the importance of proper attribution in magic and how easily errors can propagate through the literature when authors neglect to verify their sources (a problem that seems rife in modern culture these days, sadly). It took 28 years for this mistake to be corrected! This is particularly ironic given that Vernon himself was renowned for his meticulous attention to detail, especially when crediting the originators of moves, tricks and sleights.

The Core Method

At its heart, “Revolving Aces” relies on a clever application of Henry Christ’s force, performed not once but four times in rapid succession. This technique, combined with a secret arrangement of six cards on top of the deck (the four Aces and two indifferent “cover” cards), creates what appears to be a series of entirely free choices. However, it ensures the Aces appear precisely where the magician wants them.

The Christ Force, which Ted Annemann dubbed “The 203rd Force” (after including 202 other forcing techniques in his 1931 book dedicated to the subject), first appeared in print in Annemann’s 1934 booklet Sh-h-h--! It’s a Secret. The force is remarkably direct: a spectator is asked to cut the deck anywhere they like, and the cut is immediately marked by turning the upper portion face up. When they later turn over the top card of the lower portion, they’ve seemingly made a completely free selection—yet the magician knows exactly which card they’ll find, much to the audience’s surprise.

This elegant forcing technique would later inspire the more widely-known Cut Deeper Force, achieving a similar result without requiring special cards (Christ’s original handling utilises a double-backed card). However, it’s Christ’s basic method that Zarrow employed so brilliantly in “Revolving Aces”, creating a routine where each selection seems completely fair yet is entirely under the performer’s control.

Revolving Royal Flush

“Revolving Royal Flush” in Zarrow: A Lifetime of Magic by David Ben (see page 92) addresses a minor issue with “Revolving Aces”. At the end of the routine, an indifferent card remains face up in the deck. Reversing this card is a mere trifle, but why not incorporate it into the effect? This is exactly what happens in “Revolving Royal Flush” (see the video performance below by David Britland).

This version of the effect is particularly effective when performed for individuals who regularly play Poker. You can read the full details of David Britland’s handling in Cardopolis Newsletter #14.

Revolving Aces Lead-In

Another minor issue with Zarrow’s original “Revolving Aces” routine is that it requires a complicated prearrangement. If you begin a card set with this trick, this becomes irrelevant, but it renders the routine less practical in other contexts. Vernon addressed this by reinserting the Aces into the pack while it was behind his back. Although this method works, I’ve never liked handling cards behind my back (or from the audience’s view); most people realise you’re up to no good!

However, my friend, and underground cardman, Justin Higham solved this problem in typically ingenious fashion back in 1985! In his booklet All Hands on Deck, he details a simple way to set the deck right in front of an audience:

The following idea allows you to cleanly place the four Aces into different parts of the deck before going into Herb Zarrow’s “Revolving Aces” (Close-Up Card Magic, Lorayne, pp. 98-100).

The deck is face down in the left hand, the card 2nd from the top is face up. The four Aces are on the table face up.

Cut off about a quarter of the deck and table it to your left. Cut off another quarter and place it to the right of the 1st packet. Cut the remaining cards in half and table the two portions to the right of the other two. (If you like living dangerously then allow the spectator to do the cutting. What I do is to cut the 1st portion ‘to show the spectator what to do’, then allow her to do the rest of the cutting).

Pick up the pile on the left (i.e., the one with a face-up card 2nd from the top) with the left hand. Place one of the Aces face down onto the packet. As you reach for the 2nd packet take a break under the face-up card, then place the right-hand portion face up onto the left hand cards. Immediately turn all the cards above the break face down onto the remaining cards.

Pick up the 2nd Ace at the same time taking a break under the top three cards. Place the Ace face down onto the packet as before, then pick up the 3rd pile and place it face up onto the left-hand cards. Once again flip all the cards above the break face down.

Take a break below the top four cards and repeat the whole process with the 3rd Ace and the 4th packet. After this the order should be: A, X, X, A, A (underlined cards face up).

Place the last Ace face down onto the deck and execute any False Cut followed by a False Shuffle.

The cards are now set for the Zarrow routine.

Justin’s idea means you can now perform “Revolving Aces” at any point with a shuffled deck in use. Thanks, Justin!

Albion Aces

Years ago, when I became passionately interested in card magic, I accidentally reinvented “Revolving Aces” and “Revolving Royal Flush” while experimenting with the Christ Force. I was disappointed to discover that Herb Zarrow had beaten me to the punch by over forty years! Nevertheless, I continued exploring the core concept that makes “Revolving Aces” work— “Albion Aces” is my latest attempt to create something based on the idea worthy of publication.

The routine employs Justin’s method of arranging the deck. However, I have adapted his idea to the Royal Flush ending. The Royal Flush cards are positioned under the guise of inserting the four Aces into various parts of the deck. I have also developed a playful approach to presenting the effect as a demonstration of the mystical art of manifestation, a popular pseudoscientific trend among younger people these days.

High Card to Hell 🔥

Here’s another routine based on the “Revolving Aces” principle I recently published in Marty’s Magic Ruseletter (see Tricks, Tricks & More Tricks: Satanic Sorcery for full details). This is possibly my favourite way to use the Christ Force to date.

In the routine, two spectators portray a down-on-his-luck gambler and the Devil in disguise, while you take on the role of a handsome magician! The gambler draws three sixes (666) against the Devil’s Seven of Clubs. The Devil then demands the four Aces for the gambler’s soul, but one Ace, the Ace of Clubs, is missing (hidden in Satan’s pocket). As a master illusionist, you locate three of the Aces and magically transform the Seven of Clubs into the missing Ace, defeating the Devil at his own game!

I hope you enjoy learning, practising and performing these two routines based on Herb Zarrow’s “Revolving Aces”.

Yours Magically,

Marty

P.S. I encourage you to explore Henry Christ’s force. It has many applications. For example, it can be used as a very convincing switch. Look out for more routines using this powerful concept in the future.

A month after the Genii article appeared, Nick Trost published 'Ace Stop', another iteration of the same basic revolving effect, in The New Tops (June 1961). Whether Genii came out on time back then I don't know, but I wouldn't mention this if it weren't for the fact that Trost appears to be the first to apply a reversed card to the ending. His set-up had 2 Aces FD, 1 X card FU, 2 Aces FU, deck FD. He 'revolved' three times then cut the deck to bury the last reversed Ace. Ribbon Spread to reveal the face-up Ace then show other three Aces.