Monthly Update #31 (July 2025)

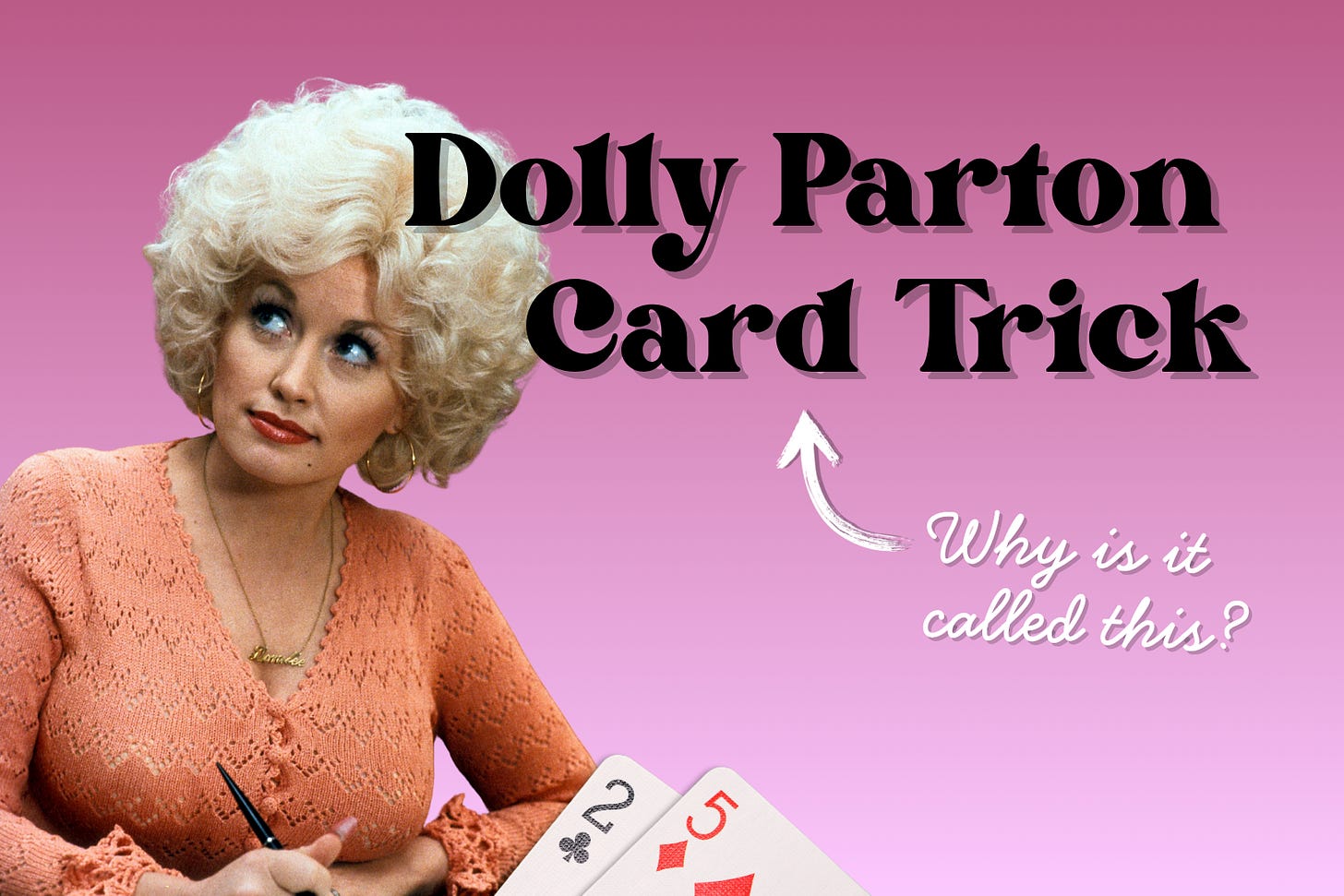

Dolly Parton Card Trick (FREE) & the Paradox of Performance

Welcome to the July monthly update for Marty’s Magic Ruseletter. This month, we’re diving deep into the philosophical mysteries that make magic, well, truly magical—and I promise it’s not as dull as it sounds! We’ll examine an academic paper titled “The Experience of Magic” that reveals why your best performances don’t just deceive people; they create a unique mental state that we still don’t fully understand.

Plus, I’m sharing an entertaining card trick with an unusual musical revelation. This simple, self-working card trick, based on an idea by creative card magician Ollie Mealing, will have your audience humming Dolly Parton for days!

For once, this edition actually landed in your inbox on schedule (miracles do happen!), and I’m excited to share more magical discoveries with you that could transform how you think about every performance you give.

Ready to peek behind the curtain of consciousness itself? Let’s explore what happens when minds encounter the impossible...

The Experience of Magic & the Paradox of Performance

Reading Time: 11 minutes

This month, I have been reading an intriguing (and reasonably accessible) academic paper called “The Experience of Magic” by Jason Leddington, Professor of Philosophy at Bucknell University. Jason does research into two interconnected areas: the aesthetics and philosophy of art, as well as the philosophy of perception. The paper was first published in The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism (Summer 2016, Vol. 74, No. 3).

The article aims to initiate a philosophical exploration of the experience of magic, emphasising its cognitive aspects. This focus on what happens in the spectator’s mind is crucial for understanding why magic deserves serious consideration as an art form. While Leddington acknowledges that magic has fallen from cultural prominence and is often dismissed as frivolous entertainment, he argues that this dismissal stems from a fundamental misunderstanding of what magic actually does in the brain. By examining how audiences truly experience magic—the unique mental states it creates and the sophisticated cognitive processes it engages—their experience can begin to reveal why magic is far more than simple trickery and deserves to be elevated as a legitimate theatrical art. For amateur magicians, understanding these cognitive mechanisms isn’t just academically interesting; it’s essential for creating performances that genuinely move and astonish audiences rather than merely puzzling them.

The paper is behind a paywall, so I’ve included some of my thoughts and observations from my initial reading of it in this update (I will need to reread it to grasp all the information and ideas in it, as is the case with most academic content like this).

An Art Deserving Dismissal

Leddington begins his paper by outlining the cultural reality facing magic today (well, ten years ago, at least). Once among the most popular and profitable forms of public entertainment, magic is now widely ridiculed as sideshow entertainment or confined to children’s parties rather than being regarded as a serious art form (for the record, I don’t think there’s anything wrong with magic for children, but it isn’t high art). He correctly points out that this shift is, in part, due to the rise of film and television. Coupled with the scarcity of genuinely skilled, theatrically refined practitioners, all indications point to what he describes as an “art” that is deserving of dismissal.

As mentioned, this paper was written almost a decade ago, but this brutal assessment of magic still made me pause for thought. Is magic still an art worthy of nothing but neglect? If so, what specific actions should both amateur and professional magicians take to address this commonplace degradation of magic as an art?

Leddington considers this situation unfortunate and argues that, as a result, the world is lacking something philosophically significant. The paper then proceeds to analyse different definitions of the perception of magic, drawing extensively from theories proposed by Teller, the silent half of the magic duo Penn & Teller, the late magician and gambling expert, Darwin Ortiz, and Tamar Szabó Gendler, an American academic and philosopher specialising in thought experiments, imagination, and the phenomenon of imaginative resistance.

The Paradox of Performance

In the article, Leddington identifies a fundamental paradox in how we experience magic:

We simultaneously believe and disbelieve what we’re seeing.

We know impossible events aren’t happening, yet we experience them as if they are.

This creates a unique cognitive state that existing theories struggle to explain.

This “paradox of performance” reminded me of a well-known theory from film and literature, known as the “Paradox of Fiction”, that relates to the suspension of disbelief (Leddington makes brief mention of this theory in his paper). Suspension of disbelief, a term first introduced by British Romantic poet and critic Samuel Taylor Coleridge, refers to the act of accepting something as real or believable despite knowing it is not, especially when engaging with a work of fiction or a theatrical performance. It involves a willingness to momentarily set aside logical doubts and critical thought to fully immerse oneself in a narrative or experience, fostering enjoyment and emotional connection with the story, characters, or performance.

However, when I watch a movie, even a good one, I don’t entirely suspend my disbelief; otherwise, I’d run for my life when the Tyrannosaurus Rex charges at the screen during Jurassic Park! 🦖 Noël Carroll, a leading figure in the contemporary philosophy of art, popularised the idea of the Paradox of Fiction in his paper “The Nature of Horror” in The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism (Autumn 1987, Vol. 46, No. 1, pages 51-59). We know the characters do not exist, but we still feel scared when watching a good horror film, even though an emotional response depends on beliefs about existence.

Comparing a movie to magic, to some extent, is a false equivalence because the paradox is different—the magical event actually happened. The spectator saw it occur. Maybe even felt it happen. It existed. It is this paradox that Leddington spends most of his paper discussing.

So, what exactly is the Paradox of Fiction? When we watch a film, attend a performance of a theatrical play, or read a novel:

We have emotional responses to fiction.

Emotional responses require beliefs about existence.

We don’t believe fictional entities exist.

Carroll’s solution to the paradox involves rejecting premise 2. It proposes that we generate something called “thought-emotions” that are triggered merely by contemplating the content rather than genuinely believing in it. For example, when we fear for a character, we do not honestly believe they exist; we are responding to the thought content itself. Many scholars reject Carroll’s solution, the primary alternative theory being fictional reappraisal, which adopts the belief that the event is not real, such as it’s “just a movie,” “just my imagination,” or “just a trick”. (This theory disagrees with all three of the above premises and is, perhaps, more applicable to the performance of magic.)

According to the Paradox of Performance, here’s what happens when we witness a magic trick:

We have an emotional response to a magic trick.

Emotional responses require beliefs about the impossibility of what we’re witnessing.

We believe what we’re witnessing is possible through some form of trickery.

This is similar, yet different. Rather than creating “thought-emotions”, spectators often develop “false solutions” to the magic tricks they encounter, or experience such a powerful emotional reaction that they stop trying to understand how the trick works. In other words, they attempt to resolve the cognitive dissonance that a good magic trick generates. For some individuals, remaining in this state can be uncomfortable, frustrating, and even distressing. Most eventually give up or, in a worst-case scenario, guess the correct method!

A Definition of Magic

Leddington begins by trying to answer the question “What is magic?” He introduces Teller’s definition of magic: that it is a form of theatre that depicts impossible events as though they were really happening. Teller’s definition is valuable because it frames magic as a form of theatre rather than charlatanry, makes no mention of deception as the primary goal, and concentrates on the portrayal or depiction of impossibility.

Based on his philosophical analysis, Leddington refines this to emphasise that magic creates a unique experiential state where audiences simultaneously experience impossibility while maintaining disbelief. It’s not just about depicting impossible events, but about stimulating the specific cognitive and perceptual experience of witnessing the impossible. Or, as he puts it, presenting impossibilities as impossibilities.

Misconceptions of Magic

The paper also identifies two common misconceptions of theatrical magic:

That magic is primarily about fooling an audience. Many people believe that a magician’s primary goal is to deceive and trick others.

Magicians want audiences to believe in supernatural powers. People think magicians are trying to convince audiences that they genuinely possess supernatural or mystical abilities.

While some performers may focus on trickery, serious magicians view deception as a means, not an end in itself. As Darwin Ortiz explains, magic isn’t just about deceiving—it’s about “creating an illusion, the illusion of impossibility.” The deception serves the larger artistic purpose of creating a specific type of theatrical experience.

Most legitimate magicians explicitly don’t want audiences to believe the magic is real. This is because genuine belief in supernatural powers actually undermines the aesthetic experience they’re trying to create. Leddington notes that “the audience’s active disbelief is a critical ingredient in the experience of magic”—the tension between knowing it’s not real while still experiencing wonder is central to what makes magic work as an art form.

Both of these misconceptions overlook the critical point that theatrical magic is about creating a sophisticated aesthetic experience that depends on the audience being simultaneously aware of the impossibility while still being emotionally moved by the performance. It’s the cognitive tension between disbelief and wonder that creates the unique experience, Leddington argues, which is philosophically significant.

Before your next performance, ask yourself: Am I focused on fooling my audience, or am I creating the experience of witnessing impossibility? There’s a crucial difference—one leads to mere puzzlement, the other to genuine astonishment.

Three Hypotheses

Leddington examines three potential explanations for what cognitive attitude is involved in the experience of magic. The first hypothesis (H1) suggests that magic essentially involves “willing suspension of disbelief”—a view widely accepted by practising magicians. However, Leddington argues this is false because suspending disbelief relegates magic to the realm of fantasy, preventing audiences from actually witnessing apparent impossibility. Using Ortiz’s example, which compares Peter Pan (where seeing wires doesn’t ruin the experience) to Copperfield’s flying illusion (where seeing wires destroys it), he demonstrates that magic requires active disbelief rather than suspended disbelief.

The second hypothesis (H2), proposed by Teller, suggests magic involves “unwilling suspension of disbelief”—capturing the involuntary nature of our response to well-executed performances. While this addresses the non-voluntary aspect, Leddington maintains that any form of suspension of disbelief misses the point by relegating impossible events to fantasy rather than allowing them to be witnessed. He emphasises that active disbelief is essential—audiences should disbelieve what they’re seeing is possible while still experiencing it as if it were happening, creating the cognitive dissonance fundamental to the enjoyment of magic.

The third hypothesis (H3) proposes that magic essentially involves a “conflict of belief”—that successful performances prompt audiences to both believe and disbelieve the impossible. Leddington rejects this because audiences don’t actually come to accept contradictions, no matter how good the performance. The experience isn’t one of inadvertent self-contradiction but rather a different type of cognitive dissonance that doesn’t demand resolution on pain of contradiction. This leads him to argue that the correct account must include cognitive dissonance that isn’t a matter of conflicting beliefs, setting up his introduction of Gendler’s concept of “belief-discordant alief”.

Alief and Astonishment

Leddington settles on a theory (H3) of the experience of magic based on a mental state called “alief”, as proposed by Tamar Szabó Gendler.

The experience of magic essentially involves a belief-discordant alief that an impossible event is happening.

The term alief refers to a feeling or intuition that may not align with what someone intellectually knows or believes to be true. It’s a primitive, subconscious, belief-like attitude. It’s not the same as a belief, but it can influence behaviour and emotions in the same way.

Aliefs act in conflict with conscious beliefs. For example, you might know intellectually that a transparent balcony is safe, but your alief might cause you to feel fear or unease while standing on it.

Think about your most successful performance: Can you identify the moment when your spectator stopped trying to figure out the method and simply experienced the impossible? That shift from intellectual analysis to emotional response is alief in action, and recognising it can help you strengthen the underlying structure of your routines.

Conjuring and Cognition

The final section of the paper provides a detailed exploration of what it feels like to experience magic. Philosophers refer to this as phenomenological analysis, an approach that focuses on the study of consciousness and the objects of direct experience. It describes the cognitive conflict that occurs when the mind struggles to reconcile sensory input with prior knowledge.

Leddington argues that magic works by “cancelling methods”—systematically eliminating all plausible explanations spectators might devise (an idea popularised by Daryl, the Magician’s Magician). Using Copperfield’s flying illusion as an example, he shows how each stage cancels potential methods (wires, boards, magnets) until spectators reach total bafflement with no way to rationalise what they’re seeing. The experience of magic occurs only when audiences have a belief-discordant alief in the impossible that they cannot explain away. This creates an “intellectual process” where what begins as a puzzle becomes an impossible event.

Consider your signature effect: Are you merely hiding your method, or are you systematically eliminating every logical explanation your audience might consider? Take a moment to list the methods a spectator might suspect—now ask yourself how your presentation addresses each one.

Leddington draws parallels between this experience and both Immanuel Kant’s theory of the sublime, cognitive failure followed by mastery of the illusion (because the spectator knows it is “just a trick”), and Socratic aporia (systematic elimination of possibilities leading to bafflement). Like Socrates’s interlocutors, magic spectators don’t abandon the idea that an explanation exists—they’re left with the attitude “there must be an explanation, but I have no idea how there could be,” creating what magician Whit Haydn calls “a burr under the saddle of the mind.”

The next time you perform, carefully observe your audience’s reactions. Can you spot the moment they move from “How did he do that?” to “That’s impossible?” That transition—from puzzle to paradox—is where the real magic happens. Are your performances supporting this shift in mindset?

Leddington argues for taking magic seriously as a subject of philosophical inquiry and demonstrates how phenomenological methods can illuminate aspects of experience overlooked by cognitive science. He suggests magic as a valuable test case for theories of perception and consciousness. He contends that understanding magic experience is important not just for philosophy of mind, but for:

Aesthetics (what makes performances compelling)

Epistemology (how we form beliefs about what we perceive)

Philosophy of art (magic as a legitimate art form)

Cognitive science (mechanisms of attention and belief formation)

The paper establishes magic as a legitimate and vital area of philosophical research, arguing that the unique cognitive-perceptual experience it creates cannot be reduced to simpler categories, such as illusion or deception. Magic represents a distinct phenomenon that reveals essential features of human consciousness and perception.

Ultimately, Leddington’s article argues that magic challenges traditional boundaries between perception and cognition. It exposes limitations in our understanding of how knowledge relates to experience. He concludes that the study of magic can shed light on broader questions about consciousness, attention, and belief.

What adjustments will you make for your next performance? How will you transition from being a puzzle creator to an architect of impossibility?

If you enjoyed reading my thoughts on this article, Jason Leddington has written a similar piece called “Magic: Art of the Impossible”, which covers much of the same ground (you can download the PDF below).

Learn the Dolly Parton Card Trick

Reading Time: 7 minutes

The “Dolly Parton Card Trick” is a delightfully entertaining prediction effect that combines the mathematical certainty of the Count-Back Force with a humorous and memorable musical reveal. The trick draws inspiration from the ingenious mind of creative card magician Ollie Mealing and his effect, “Everyday”, which was featured in Mealing’s Mail - Entry No. 6 (July 2025). Mealing’s original concept employed a different forcing principle to create a “24/7” prediction (a pile of twenty cards combined with a Four and a Seven spot).

Here’s what happens: A spectator selects any two-digit number less than twenty, and cards are dealt accordingly. Through a series of seemingly random actions—including the “burning” of cards—the performer arranges events to reveal exactly nine cards remaining in a pile, with a Two on top of the pile and a Five on top of the deck. The big reveal? “Nine, Two, Five—my favourite Dolly Parton song!”

The trick offers numerous advantages. It is almost self-working, as the mathematical principle does most of the hard work—the trick practically performs itself once you understand the concept! Additionally, it requires minimal preparation; you only need a standard deck of cards and a simple setup: place any Two on top and then move any Five ten cards from the top. The trick also elicits strong reactions from an audience, creating a moment of recognition and laughter. Moreover, the presentation is flexible; it can be adapted into the “Office Hours Card Trick” for younger audiences who may not be familiar with the 1980s song or Dolly Parton.

This trick is ideal for magicians of all skill levels. Beginners will appreciate its self-working nature, intermediate performers can enhance it with false shuffles and cuts, and advanced magicians can explore the more intricate setup variations provided (or substitute a different sleight-of-hand method entirely). By learning this trick, you’ll gain a better understanding of the powerful Count-Back Force principle, which can be applied to many other effects. The routine also teaches valuable lessons in presentation and how a strong reveal can elevate a simple mathematical force into a memorable moment of magic.

The “Dolly Parton Card Trick” proves that effective magic doesn’t need to be complicated. With no (or a little) sleight of hand, minimum preparation, and a charming presentational hook, you’ll have a reliable crowd-pleaser that works every time without fail. The combination of mathematical certainty and musical nostalgia makes this an ideal addition to your card magic repertoire.

Although I published it in an odd-numbered edition of Easy Does It, I have decided to make the write-up accessible to everyone, whether you are a paid subscriber or not. I’ll also be releasing more work on the Count-Back Force soon, including a different presentation for this method that involves tea and biscuits! ☕🍪

Read Easy Does It #5: Dolly Parton Trick 👈

Three Videos Worth Watching 👀

Since we explored Ollie Mealing’s brilliant “Everyday” concept in the “Dolly Parton Card Trick”, I thought you’d enjoy seeing more of his creative approach to card magic. Here are three of his most popular YouTube videos—all techniques he teaches in depth within The Mealing Experience. (If you subscribe using the button below, you’ll get a 25% discount on the regular price of a monthly subscription.)

Each video showcases different aspects of what makes Ollie’s work special: natural performance style, creative presentations, and innovative thinking about when and how the magic should unfold.

Coffee & Card Tricks

Duration: 3 minutes

Watch Ollie perform his outstanding personal handling of “Henry Christ’s Fabulous Ace Routine” over a cup of coffee with a friend. Notice how effortlessly he weaves the magic into genuine interaction.

Compass 🧭

Duration: 6 minutes

A superb example of Ollie’s gift for developing memorable presentations. This conversational card trick demonstrates what we discussed about creating genuine astonishment rather than just mere puzzlement. The compass metaphor adds emotional depth, ensuring the effect will be remembered for a long time (it also distracts from possible methods).

Serendipity

Duration: 3 minutes

One of Ollie’s most requested effects, and you’ll understand why immediately. The staging is wonderfully unconventional—the magician isn’t even present for the final revelation! It’s a masterclass in delayed gratification and proves that sometimes the most powerful magic happens when you’re not even at the table or in the room.

That’s all for another month. Thank you for reading. Remember—focus on creating impossibility, not just hiding methods.

Yours Magically,

Marty