Legends of Legerdemain #2: Count Caligstro

The eighteenth-century Masonic magician, occultist, healer and alchemist.

For this instalment of Legends of Legdemain, I’ve decided to investigate the eventful life of Count Alessandro di Cagliostro, whom I briefly mentioned in my previous article on Professor Pinetti. While Pinetti was a celebrated conjurer during the eighteenth century, Cagliostro (pronounced “kaly-o-stro”) was an adventurer who dabbled in the occult, including psychic healing, alchemy and scrying. He was also accused of being a quack, con man and even murderer! Depending on who you ask, opinions on him vary greatly.

Although there are indications that he utilised tricks and magical illusions to advance his career, he differed from his contemporaries—such as Pinetti, Comus, and Katterfelto—because he didn’t perform as a self-proclaimed scientific wonder-worker. Instead, he presented his powers as supernatural or divine in nature, using them in his quasi-religious Séances. Nonetheless, his influence on the performance of magic during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries was noteworthy.

Additionally, he was a prominent member of the Freemasons and established his own version of “Egyptian Freemasonry”, which, despite its name, had little to do with Egypt. Unfortunately, it was his involvement with this secretive organisation that ultimately resulted in his downfall at the hands of the Roman Inquisition. He was imprisoned in the fortress at San Leo in 1789, where he died six years later on the 26th of August, 1795.

Cagliostro’s Casket

Even years after his passing, the legacy of the Count of Cagliostro continued to flourish, thanks to magicians like the renowned Father of Modern Magic, Jean-Eugène Robert-Houdin.

During one of his performances, the famous French magician amazed the King of France, Louis Philippe I, with the help of Cagliostro from beyond the grave. Robert-Houdin asked the members of the royal court to lend him their handkerchiefs, which he then bundled together. The audience wrote various locations for the handkerchiefs to reappear on slips of paper. Three slips were selected, and then the King chose one of them. The location he selected was the chest of the last orange tree on the right of the avenue. Robert-Houdin made the handkerchiefs vanish from beneath an opaque glass bell, replacing them with a white turtle dove. His audience was awestruck, and the King reportedly remarked, “There is decidedly witchcraft about this.”1 A box was found below the roots of the indicated orange tree. In it was a parchment, which read:

THIS DAY, THE 6TH JUNE, 1786,

THIS IRON BOX, CONTAINING SIX HANDKERCHIEFS, WAS PLACED AMONG THE ROOTS OF AN ORANGE-TREE BY ME, BALSAMO, COUNT OF CAGLIOSTRO, TO SERVE IN PERFORMING AN ACT OF MAGIC, WHICH WILL BE EXECUTED ON THE SAME DAY SIXTY YEARS HENCE BEFORE LOUIS PHILIPPE OF ORLEANS AND HIS FAMILY.

In the decades after his death, Cagliostro continued to inspire magicians. His exotic-sounding name has frequently been used by conjurers and stage magicians to add an heir of mysticism to their magic tricks. For example, there is an effect in August Roterberg’s New Era Card Tricks, published in 1897, called “The Hand of Cagliostro”, in which an imitation hand (made out of papier mache) eerily plucks several chosen cards from the pack. Similarly, in his 1910 book simply titled Magic, Ellis Stanyon suggested that "Cards of Cagliostro" would be a suitable name when presenting the Rising Cards to an audience.

Adelaide Herrmann, the English magician and vaudeville star, performed a magical skit called “Cagliostro”, in which she impersonated the celebrated sorcerer of the Ancien Régime.

In 1889, Georges Méliès, the noted stage magician and early pioneer of cinema, also performed an illusion at the Théâtre Robert-Houdin called “La Fée des Fleurs ou le Miroir de Cagliostro”, also known as “Cagliostro’s Mirror”. In 1891, Hercat, real name R. D. Chater, and Colonel H.J. Sargent, known as the “Wizard of the South”, went one step further and opened an entire magical show in London called the “Cagliostromantheum”. Two years later, in 1893, an illusionist named M. Caroly presented a devilishly clever trick called the “Mask of Balsamo” during his conjuring exhibition at the Capucine Theatre in Paris. Henry Ridgley Evans, a magic historian and amateur magician, witnessed the performance:

The prestidigitator brought forward a small, undraped table, which he placed in the centre aisle of the theatre; and then passed around for examination the mask of a man, very much resembling a death-mask, but unlike that ghastly memento mori in the particulars that it was exquisitely modelled in wax and artistically coloured. ‘Messieurs et mesdames,’ remarked the professor of magic,‘this mask is the perfect likeness of Joseph Balsamo, Comte de Cagliostro, the famous sorcerer of the eighteenth century, modelled from a death-mask in the possession of the Italian Government. Behold! I lay the mask upon this table in your midst. Ask any question you please of the oracle and it will respond.’ The Mask rocked to and fro with weird effect at the bidding of the conjurer, rapping out frequent answers to queries put by the spectators. It was an ingenious electrical trick!2

Charles Jordan, the prolific magical inventor and author, published a fantastic card trick called “Cagliostro’s Vision” in The Encyclopedia of Card Tricks (initially released in 1936).3 The description of the trick doesn’t include any suggested patter, or make reference to Cagliostro directly, but it is a fine location effect, typical of the genius that was Charles Jordan. The title chosen demonstrates that the name Cagliostro was still synonymous with magic and mystery more than a century after his death!

More recently, an apparatus trick called the “Skull of Cagliostro” was created by Brad Toulouse and released by Mephysto Magick Studio. In it, a small replica skull—an apparent keepsake from the dead Count’s estate—is “imprisoned” by being threaded onto a red silken cord. The cord symbolises the great man’s incarceration in the Fortress of San Leo. The magician then uses “magick” to mysteriously release the skull from its bondage, somehow penetrating the cord, which remains intact!4

Houdini, arguably still the world’s most famous magician to this day, was also fascinated by Cagliostro. In particular, he was interested in his apparent involvement in the Affair of the Diamond Necklace (more about this later). He collected every available scrap of information on the case when he visited Paris in the early nineteen hundreds. Harry and Bess even rented a flat at 32 Rue de Bellefond in the 9th arrondissement of Paris so that Houdini could walk in the footsteps of his magical heroes.5 Harry managed to locate Cagliostro’s former home and discovered a hidden staircase that the Count may well have used to perform one of his most well-known spiritual séances.

Ghostly Guests at the Dinner Party 👻

One of the most famous and intriguing stunts performed by Cagliostro is the Cénacle de Treize or Banquet of the Dead. According to the Marquis de Luchet, Cagliostro invited six noblemen for dinner, but curiously, he set the table for thirteen. Upon their arrival, Cagliostro asked each guest to name a famous deceased historical French figure to occupy the empty seats at the table.

As soon as their names were mentioned, spectres of the Duc of Choiseul, Abbé de Voisenon, Montesquieu, Diderot, d'Alembert, and Voltaire appeared, much to the surprise of Cagliostro’s wealthy guests. The ghostly apparitions conjured up by the Count joined the shocked diners at the table, and a sumptuous meal was served to all thirteen guests. The ghosts engaged the nobleman in conversation late into the night and then disappeared.

This story is mentioned in Cagliostro: The Splendour and Misery of a Master of Magic. According to the book's author, W.R.H. Trowbridge, the anecdote in question has no foundation in reality and was most likely a product of the Marquis de Luchet's vivid imagination.6 However, even though it may not have occurred exactly as described, the banquet for France's “great ghosts” was widely discussed in Paris and was even a topic of conversation at the royal court in Versailles!

Stories like the one mentioned above helped to strengthen, enrich and solidify Cagliostrio's status among the French elite as a divine prophet able to heal the sick, raise the dead, travel through time and predict the future!

Cagliostro’s Early Life

Many historians believe that the true identity of Count Cagliostro is Giuseppe Balsamo, who was born in Palermo, Southern Italy, in 1743. Also known as Joseph Balsamo, he was a petty criminal who engaged in activities such as forgery, theft and deception. However, this claim was based on a single, questionable source—a sensational newspaper article written by Charles Theveneau de Morande, himself a notorious pornographer, scandalmonger, extortionist and suspected French spy!

Cagliostro always insisted that this story of his early life was not true. He admitted that he didn’t know the names of his parents or his birthplace in his memoirs. However, he did assert that they were of noble birth and followers of Christianity. He also claimed that, at the age of three months, he was abandoned as an orphan, possibly on the island of Malta. Throughout his life, the Count maintained that he was raised by various dignitaries and his mentor, the nobleman and alchemist Althotas7.

A reasonably credible theory about his parentage, however, was put forward in the pages of the Courier de l’Europe, a bi-weekly Franco-British periodical published from 1776 to 1792 (the very same newspaper that ran the scandalous story on Cagliostro written by Theveneau de Morande). Parkyns Macmahon, a former sub-editor of the paper, stated with great authority that Cagliostro was the son of the Prince and Princess of Trebizond (now part of modern-day Turkey). At the age of three, Cagliostro’s father, the reigning Prince, was killed during a revolution. Fortunately, one of the Prince’s friends helped smuggle the young boy out of the country to the ancient city of Medina, where he was cared for by the Mufti Salahaym (a scholar of Islamic or Sharia law).

As a child, Cagliostro was known as Acharat and was attended by three servants and his mentor, Althotas, who was knowledgeable in Eastern philosophies and alchemy. In 1760, at the age of 12, he embarked on travels with his mentor. They first travelled to Mecca, where they lived for three years in the palace of the Sherif.8

In 1763, Acharat and Althotas travelled to Egypt to study the sacred teachings of the ancient Egyptian priests. Afterwards, they continued their journey to Asia and Africa, finally landing on the island of Malta. It was here that a young Cagliostro met Pinto, the Grand Master of the Knights of Malta. Acharat and his mentor Althotas spent some time at Pinto’s palace. During this time, Acharat practised the sciences, and Althotas earned the insignia of the Order of the Knights of Malta. Some historians believe that Cagliostro's father was Pinto himself and that his mother was a noblewoman from Trebizond; in fact, Cagliostro suggested much the same in his own memoirs. It was during this time that Acharat assumed the name of Count Cagliostro and the dress of a European.

Unfortunately, Althotas died while he and Acharat were in Malta. After losing his master, best friend, and surrogate father, the young Cagliostro felt empty and found his life on the island without purpose. As a result, he decided to embark on further travels once again, this time with the Chevalier Luigi d’Aquino. The pair visited Sicily and other islands of the Italian archipelago, finally landing in Naples, the home country of the Chevalier Luigi d’Aquino.

Cagliostro then departed alone to Rome, where he met Cardinal Orsini and Pope Clement XVI. Whilst there, at the ripe age of 22, he also met a beautiful young girl called Seraphina Feliciani. He fell desperately in love with the 15-year-old and persuaded her father, a prominent Roman merchant, of his good intentions. The pair were married soon after.

So which story is true? Was Count Cagliostro a forgotten prince of Trezibond or a lowlife criminal from Palermo? The evidence supporting the theory that Cagliostro was actually Giuseppe Balsamo is not particularly strong. Additionally, it's worth noting that the memoirs written by Cagliostro cannot be considered entirely reliable either, much in the same way that large portions of the memoirs of Jean-Eugène Robert-Houdin have been discovered to be entirely fictional!

Given Balsamo’s supposed notoriety across Europe, it’s difficult to imagine that the authorities in Italy, Egypt, France, and England all failed to identify him as Cagliosto. It is also striking that Giuseppe and Lorenza Balsamo were never formally accused of being “the Cagliostros”, nor were Alessandro and Seraphina Cagliostro ever identified as “the Balsamos”. Although there is some evidence that Count Cagliostro and Giuseppe Balsamo could be the same person, the available information is inconsistent and comes from unreliable sources, such as the writings of Giacomo Casanova and the public records of the Roman Inquisition. In reality, it's unlikely we'll ever know the true identity or origin of the mysterious Alessandro, Comte di Cagliostro!

Sensational Séances 🔮

Cagliostro became well known in Europe for his apparent psychic abilities and for making eerily accurate predictions. During his mystical séances, he would use a “dove”, not a bird, but a young boy or girl (as scryer or seer) and a large globe of clarified water. To modern ears, using a child in a séance may seem odd. However, Egyptian and mediaeval magicians have been employing “doves” for centuries in ritualistic magic. A “dove” also played an important role in the Masonic initiations for both men and women in Cagliostro’s Rite of Egyptian Freemasonry. It was thought that a young child was more in touch with the spirit world, perhaps because of their innocence and purity. The child would kneel before the globe and concentrate on its liquid, inducing hypnosis and manifesting their clairvoyant abilities.

Sometimes, the Count would use a vase filled with a mixture of oil and water or a crystal sphere instead of a globe filled with clear water. He would also occasionally use a small metallic mirror that he carried with him.

Cagliostro's séances caused an absolute sensation in France. They were attended by the Paris elite, who constantly sought new and exciting experiences. He performed them at his rented house, 30 Rue St. Claude (now number 1 as the numbering was altered during the reign of Louis Philippe). The Count’s spirit séances took place within a specially furnished room in the building called the Chambre Egyptienne. The room was lavishly decorated with concave mirrors, a crux ansata (Egyptian symbol of life) and statues of ancient Egyptian deities, including Anubis—the god of embalming, mummification and funeral rites—and Isis, a central figure in the Osiris myth. The walls were decorated with Egyptian hieroglyphs.

To complete the mise-en-scène, the Count dressed in a black silk robe embroidered with red hieroglyphs. He wore an ornate jewelled turban on his head and a chain of emeralds around his neck. Attached to the chain were brightly coloured scarabs and cabalistic symbols cast in different metals. He had a sword around his waist with a handle shaped like a cross, draped from a red silken belt. In this fanciful costume, Cagliostro performed mesmeric passes, recounted cabalistic words, and called upon angels to enter the receptacle. The “dove” would then observe the visions and describe events that were happening or would soon come to pass.

Cagliostro was not a theatrical conjurer like his contemporaries, such as Professor Pinetti and Philadelphus Philadelphia. However, he provided the blueprint for the modern spirit medium and cleared the path for the likes of the Davenport Brothers almost a century later.

The Count gained immense popularity with Parisian high society in the years leading up to the French Revolution, thanks to his sensational séances. His fame was such that the renowned artist Jean-Antoine Houdon sculpted a bust of him in marble, which was replicated in bronze and plaster and sold widely. Additionally, several artists, including Francesco Bartolozzi, produced many popular engravings of “ the divine Cagliostro”, as he was known by his admirers.

Herbalist and Healer 🌿

During his time in Strasbourg, the Comte de Cagliostro was known for generously giving money to those in poverty and for his reputed ability to heal the sick using mesmeric passes, laying on of hands, and the administration of formulas and tinctures (an extract of plant or animal material dissolved in ethanol).

The Count was also famous for his beauty ointment called pommade pour le visage, which was popular among high society ladies due to its remarkable youth-enhancing effects. Additionally, Cagliostro was believed to possess the fabled elixir of life, a legendary potion that could grant the drinker eternal youth and power over life and death. The composition of the elixir was based on malvoisie wine, distilled with the sperm of certain animals and the sap of particular plants—a rather unappealing prospect. Personally, I’d prefer to age gracefully!

Count Cagliostro was a firm believer in the Paracelsian maxim, "In herbis, verbis, et lapidibus", which means "in herbs, words, and stones". He would grind different herbs, roots, and flowering plants and mix them with various powders to create herbal remedies. He would then use the power of words to heal the sick by shouting, “I desire your illness to disappear” and “I command you to be cured!” To modern ears, this all sounds faintly ridiculous and somewhat absurd. However, it may well have had a powerful placebo effect on the peasants of eighteenth-century France. In any case, giving the poor soup and money, which Count Cagliostro did frequently, would likely also improve the health of those experiencing extreme poverty!

Some sources suggest that he might even have used psychoactive elixirs and fumigants containing hashish (cannabis) during his séances and masonic rituals. There are also references to an "elixir of Saturn" that he used, but unfortunately, the recipe for it has been lost.9

The Affair of the Diamond Necklace 💎

At the pinnacle of his fame, the mysterious Count Cagliostro was abruptly arrested at gunpoint on suspicion of being involved in the notorious Affair of the Diamond Necklace. On the 22nd of August, 1785, he was forcibly removed from his home, shoved into a carriage, and hauled off to the Bastille—the infamous state prison of France during that era.

Cagliostro languished there for nine long months before being acquitted of any wrongdoing in the scam that had rocked French society. Though cleared of all charges, his reputation never fully recovered, and he wandered Europe unsuccessfully trying to regain his lost prestige. The sensational affair marked the beginning of the end for the once-admired occult figure.

So what had happened? The court jewellers, Boehmer et Bassenge, had in their possession a magnificent diamond necklace, originally designed for Madame du Barry, the mistress of Louis XV. This dazzling, gem-encrusted collar was valued at a whopping 1,800,000 livres! But “the well-beloved” King of France died before the necklace was completed. This presented a big problem for the jewellers—it became an albatross around Boehmer’s neck rather than a resplendent decoration around Du Barry's. Consequently, the royal jewellers were forced to sell it or face the very real risk of bankruptcy.

Boehmer twice offered the necklace to Marie Antoinette, but she refused to buy it on both occasions. The Queen believed France had “more need of Seventy-Fours [ships] than of necklaces.” Even her husband, Louis XVI, was not permitted to buy it. Boehmer was so upset that the poor man threatened to kill himself.

What transpired next borders on a work of fiction. Cardinal de Rohan, the bishop of Strasbourg and a known patron of Cagliostro, fell prey to an elaborate ruse orchestrated by the notorious Jeanne de Valois-Saint-Remy, better known as the Comtesse de La Motte.

Harbouring a personal vendetta against the French monarchy, La Motte devised a devious scheme to defraud the Cardinal out of a massive sum. She convinced Rohan that Marie Antoinette herself had commissioned her to purchase the resplendently extravagant diamond necklace on the Queen's behalf.

Having fallen out of favour with the royal court years prior, Rohan was eager to regain his standing in Parisian high society and the graces of the estranged Queen. Some historians posit that the manipulative Comtesse led the credulous Cardinal to believe that Marie Antoinette was secretly enamoured with him, though in truth, it was he who nurtured an unrequited obsession with her.

La Motte claimed to be a close confidante of the Queen. The Cardinal agreed to guarantee the money, to be paid off in instalments, but only if he could meet the Queen and talk with her in person. The cunning Comtesse found a prostitute called Nicole le Guay d'Oliva, who bore a striking resemblance to the Queen. She arranged for Rohan to meet with her in the gardens of the royal palace under the cover of darkness. From that point on, the Cardinal was under the control of the conspirators.

The Comtesse de La Motte instructed Boehmer et Bassenge to release the diamond necklace to her. She promptly turned it over to her husband, who fled with it to London, broke up the necklace and immediately began selling the precious gemstones.

The elaborate ruse finally unravelled when Rohan failed to make the first payment instalment and could not produce the necklace upon request. The outraged jewellers complained to the Queen herself—who professed total ignorance of the entire sordid affair.

What does Count Cagliostro have to do with all of this? Well, according to the Comtesse de La Motte, both Cardinal de Rohan and Count Cagliostro were involved in the theft. The Comtesse claimed that Cagliostro and the Cardinal summoned her to one of their séances and presented her with a casket of diamonds, with instructions to sell them in London. Following these accusations, Rohan and Count Cagiostro were arrested and imprisoned in the Bastille.

The Cardinal was tried, along with his alleged accomplices, before the Parlement of Paris. During the trial, when Comtesse de La Motte was confronted with Cagliostro’s evidence, she became so enraged that she threw a candlestick at the Count’s head in front of all the judges!

Though he was eventually acquitted, Cardinal de Rohan was deprived of all his offices and exiled to the abbey of La Chaise-Dieu in Auvergne. Count Cagliostro and his wife, though also both found innocent of any wrongdoing, were treated more harshly. They were both exiled from France by order of the King. During this time, Cagliostro was considered a martyr by the libertarians because he was unjustly imprisoned in the Bastille without trial for a long period of time. This was a clear abuse of power by the ruling elite. It's not surprising that the King, in particular, wanted to get rid of him.

The fate of the Comtesse de La Motte was not a pleasant one, and her punishment was extreme. She was sentenced to be stripped naked, publicly flogged and imprisoned for life in the Salpêtrière, a notorious prison for prostitutes. In addition to this, she was branded with the letter "V" on each of her shoulders to symbolise the French word "voleuse", meaning thief. However, amazingly she managed to escape her captors, disguised as a boy, and fled to London, where, in 1789, she published her scandalous memoirs. Unsurprisingly, she blamed Marie Antoinette for the whole affair. Two years later, while trying to avoid debt collectors, she fell from a window to her death.

Within a few years, the French Revolution began, and those who had banned the Count and his wife from France—including Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette—lost their heads to Madame Guillotine. The Affair of the Diamond Necklace had claimed its final victims!

The Comte and Comtesse di Cagliostro departed for London, never to return to their beloved France. Their house was abandoned for twenty-four years until the French government reopened its doors in 1810. At that time, an auction was held to sell off the Count's occult paraphernalia and personal possessions.

Cagliostro’s Downfall

After being exiled, the Cagliostros travelled to London. Alessandro wrote a misguided letter to the French people. In it, he complained about his treatment in prison. In the letter, he seems to predict the fall of the Batille, when he writes that he’d only return to Paris when the prison was torn down and turned into a public promenade!

He also instructed lawyers to initiate legal proceedings against the governor of the Bastille, the Marquis de Launay, for seizing and destroying his money, personal belongings, and various elixirs, potions, and powders. The case never made it to trial because Cagliostro refused to return to Paris, fearing further royal retribution or even imprisonment. In truth, the charges were highly spurious and designed to irritate the French authorities.

In London, the Count fell in with the wrong crowd and was apparently swindled out of most of his remaining money. The English were not as easily impressed or duped by his spirit séances, demonstrations of animal magnetism and transcendental medicine. As a result, he was forced to pawn most of his remaining possessions, along with most of his wife’s jewellery.

In England, Cagliostro faced a lot of criticism from the press, especially from the Courrier de l'Europe and the English Freemasons. They were not interested in his Egyptian Rite. In 1786, Cagliostro attended a banquet with some French gentlemen at the Lodge of Antiquity. During the banquet, a brother of the lodge named Mash, an Optician by profession, performed an after-dinner act in which he imitated a quack doctor selling nostrums, elixirs and balsams (Balsamos). After the performance, the other masons jeered at Cagliostro, and he left the event feeling ridiculed.

There is a rare print of a lithograph—a copy of which can be seen in the Scottish Rite Library, Washington, DC—which depicts the unmasking of Cagliostro at the Lodge of Antiquity. The following verse is appended to the engraving:

“Born, God knows where, supported, God knows how,

From whom descended, difficult to know.

Lord Crop adopts him as a bosom friend,

And manly dares his character defend.

This self-dubb’d Count, some few years since became

A Brother Mason in a borrow’d name;

For names like Semple numerous he bears,

And Proteus like, in fifty forms appears.

‘Behold in me (he says) Dame Nature’s child,

‘Of Soul benevolent, and Manners mild;

‘In me the guiltless Acharat behold,

‘Who knows the mystery of making Gold;

‘A feeling heart I boast, a conscience pure,

‘I boast a Balsam every ill to cure;

‘My Pills and Powders, all disease remove,

‘Renew your vigor, and your health improve.’

This cunning part the arch impostor acts,

And thus the weak and credulous attracts,

But now, his history is rendered clear,

The arrant hypocrite, and quack appear.

First as Balsams, he to paint essay’d,

But only daubing, he renounc’d the trade.

Then, as a Mountebank, abroad he stroll’d

And many a name on Death’s black list enroll’d.

Three times he visited the British shore,

And every time a different name he bore.

The brave Alsatians he with ease cajol’d

By boasting of Egyptian forms of old.

The self-same trick he practis’d at Bourdeaux,

At Strasburg, Lyons, and at Paris too.

But fate for Brother Mash reserv’d the task

To strip the vile impostor of his mask,

May all true Masons his plain tale attend

And Satire’s lash to fraud shall put an end.”

With the threat of debtor’s prison looming large over his head, Cagiostro had no choice but to flee, once again, to Continental Europe. However, he was prohibited from practising his particular brand of medicine and masonry in many places, including Austria, Germany, Russia and Spain.

In 1789, he foolishly went to Rome, where the Pope considered Freemasonry a capital offence. This decision seems rather odd, but it was believed that he did this partially to please his wife, who was missing her family and wanted to return to her childhood home. Cagliostro may have also chosen Rome because of its size, which would make it easier for him to continue to practice Egyptian Freemasonry and avoid detection. Even so, on the evening of the 27th of December, 1789, the Count and his wife were arrested by the Papal police and imprisoned in the Castle of St. Angelo.

The details surrounding Cagliostro’s arrest remain unclear. Some accounts state that he met two men pretending to seek initiation into his Egyptian Rite but who were actually spies for the Inquisition. However, other records suggest an alternative, more sensational theory—that Seraphina, Cagliostro's own wife, had grown weary of their vagabond lifestyle and betrayed his whereabouts to Church authorities. Regardless of the impetus, Cagliostro soon found himself imprisoned by the Roman Inquisition.

The only charge brought against Count Cagliostro was that of heresy and attempting to establish a Masonic lodge in Rome; he was not accused of anything related to occultism or any of the petty crimes or misdemeanours connected to Guiseppe Balsamo. Unfortunately for Cagliostro, two papal bulls decreed that Freemasonry was a capital offence, punishable by death.

His highly-prized manuscript of Egyptian Freemasonry was seized (and eventually destroyed), together with all his belongings, papers and correspondence. He suffered through forty-three interrogations before being tried by the Holy Inquisition.

The trial took a dramatic turn when his wife, Seraphina, testified against him. Under interrogation, she accused him of forcing her into prostitution and preventing her from practising her Catholic faith. However, the Inquisition was known to torture suspects routinely—so her claims should be regarded with a great deal of scepticism; most people, understandably, would say anything to avoid the rack. Nonetheless, her apparent betrayal and repentance did little to mitigate her own punishment. Deemed guilty alongside Cagliostro, Seraphina was condemned to spend the remainder of her life in Saint Appolonia, a Roman convent that doubled as a prison for women.

On the 7th of April, 1791, Cagliostro was condemned to death. His sentence was almost immediately commuted by Pop Pius himself (through the intervention of a mysterious visitor to the Vatican). Instead, he was imprisoned for life at the formidable mountain fortress of Forte di San Leo.

The Roman authorities were so concerned that French libertarians might try to free Cagliostro, so he was escorted by armed guards under the cover of darkness to the Papal State prison of San Leo in Urbino, Tuscany. The fortress, built upon a steep cliff, was only accessible via a treacherous stairway cut into the rock.

Cagliostro was destined for the “Pozzetto”—Forte di San Leo’s most secure and infamous cell. This damp, nine-foot square hole had previously housed only the castle’s highest-risk inmates. Carved directly into the mountainside and used initially to store drinking water, it was now enclosed within the fortress’s tower with only a trapdoor in the ceiling for access. No door, no hope of escape. The small opening served merely to lower helpless prisoners into the “well of the cell”, where they would remain isolated and entombed until death finally granted an exit. It was in this merciless void of the Pozzetto that Count Cagliostro, once so worldly and free, would draw his last breath—the mountain itself his final captor in life.

The man who had so often escaped peril in the past had finally run out of luck. On August 26th, 1795, it was reported that the adventurer and alchemist was dead. However, exactly how he died wasn’t mentioned (the location of the Count’s grave was also never disclosed). This led to the romantic notion that Cagliostro had escaped to France or Russia with his wife. Given the nature of his imprisonment—in a castle boasting walls seven feet thick and situated high above the nearest village—this idea seems improbable.

And so concludes the remarkable saga of Count Alessandro di Cagliostro, the Grand Copht of Egyptian Freemasonry—alchemist, occultist and adventurer extraordinaire. His relatively short life of only 52 years came to a miserable end in a dank and dirty hole. Though his reported crimes ranged from fraud to murder, it was membership in the outlawed Brotherhood of Freemasonry that sealed his fate. As a result, he became a target of the Inquisition’s extreme and unrelenting fanaticism. Even his supernatural powers could not help him escape the cold stone walls of intolerance. While his legend would live on, the man himself faded away and was eventually buried in an unmarked grave near that lonely mountain peak.

The fate of his wife was no less tragic. By 1794, she reputedly had gone insane and died alone behind the walls of Saint Appolonia. Though the details surrounding the trial and death of the Comte de Cagliostro remain murky, it marked a spectacular downfall for the once revered Cagliostro and the naive young woman who had been his closest companion. Their destiny was to be separated and imprisoned until madness and death finally united them again.

Cagliostro’s Legacy

After his death, his reputation suffered a great deal. The once-renowned magician became a muse for satirical mockery, his larger-than-life persona ripe for lampooning. His most potent detractors were none other than historical and literary titans:

Catherine the Great: The formidable Empress, harbouring a personal grudge against Cagliostro, immortalized him in two scathing skits, skewering his flamboyant mystique with biting wit.

Johann Wolfgang Goethe: The literary giant penned The Great Cophta, a comedic play directly inspired by Cagliostro's exploits, exposing the charlatan beneath the dazzling showman.

Alexandre Dumas: The master storyteller resurrected Cagliostro in several novels, most notably Joseph Balsamo and The Queen's Necklace, in which he claims to be 3,000 years old and have known Helen of Troy.

Aleksey Nikolayevich Tolstoy: In a twist of the surreal, the Russian author crafted Count Cagliostro, a supernatural love story where Cagliostro conjures a long-dead princess from her portrait.

Cagliostro’s legacy extended even into the world of classical music. Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart’s renowned opera The Magic Flute is thought to be influenced by the public fascination with Egyptian mysticism at the time. Music historians have suggested the noble wizard Sarastro, who triumphs over the sinister Queen of the Night, was inspired by the real-life occultist Cagliostro. During his heyday, Cagliostro’s Egyptian Rite of Freemasonry had become wildly popular among French nobility. Though his life ended in tragedy, this charismatic figure left an indelible cultural impact through works of art such as Mozart’s iconic masterpiece. Even over two centuries later, echoes of the mysterious Count can still be detected in unlikely places.

However, by the late nineteenth century, Count Cagliostro was widely considered a fraud and a charlatan. He was labelled the “Quack of Quacks” by Thomas Carlyle, an influential Victorian essayist, historian and philosopher. However, more modern historical authors, like Henry Ridgely Evans and Philippa Faulks, have portrayed him in a more sympathetic light, presenting a much more positive image of the Masonic magician.

Cagliostro is still regularly featured in novels, comic books, films and even video games. There’s even a font named after him!

The third Kid Eternity comic book, published in 1946, featured Cagliostro's risen spirit. He is also the subject of three stories by Rafael Sabatini (The Lord of Time, The Death Mask and The Alchemical Egg, which are included in his collection Turbulent Tales).

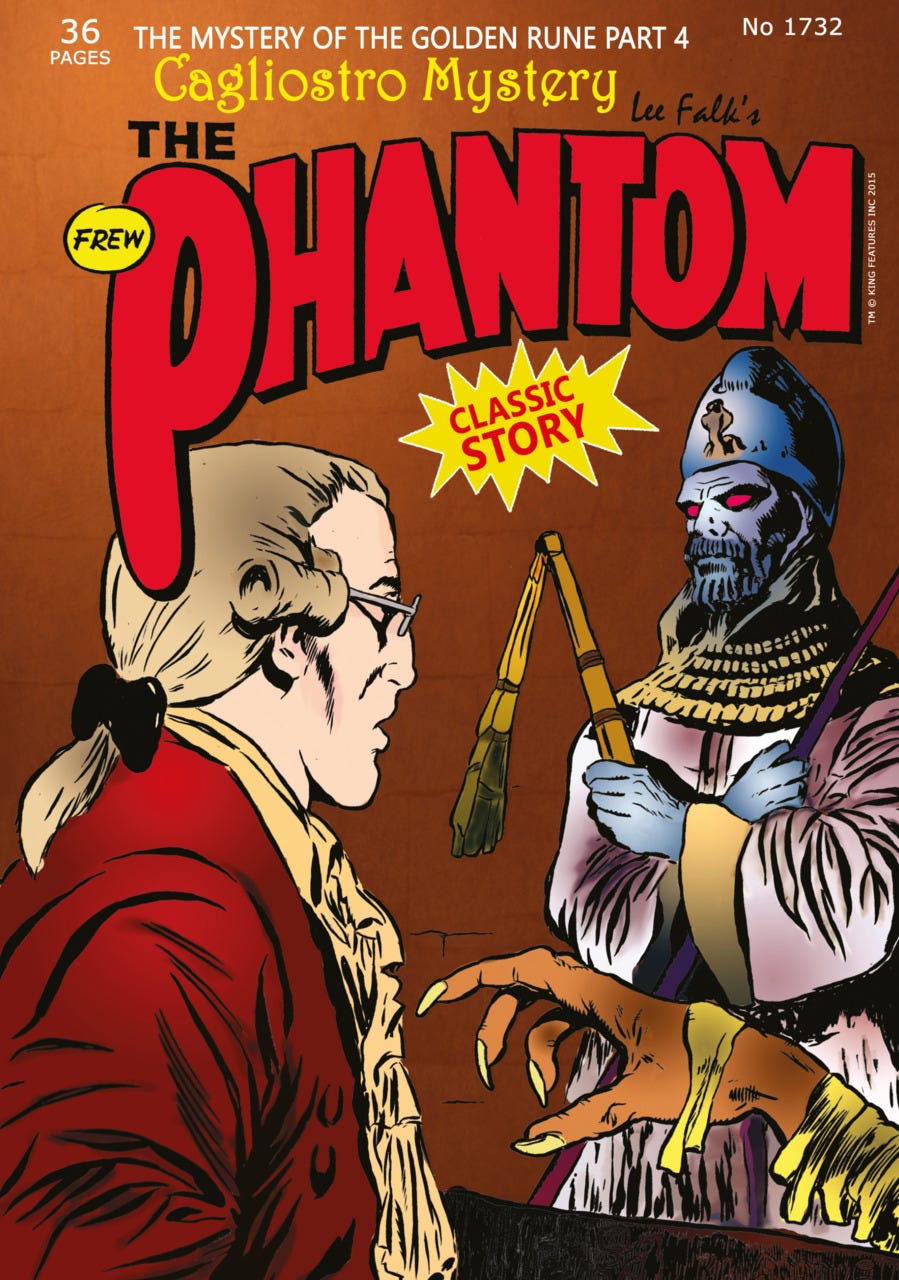

In 1988, the comic book The Phantom featured Cagliostro as a character in the story "The Cagliostro Mystery". The story was written by Norman Worker and had artwork drawn by Carlos Cruz. In the DC Comics universe, Cagliostro is described as an immortal, a descendant of Leonardo da Vinci, and an ancestor of the sorcerers Zatara and Zatanna. This information can be found in Secret Origins 27 and JLA Annual 2. Cagliostro is also a character in Tomb of Dracula and Dracula Lives by Marvel Comics, where he is frequently portrayed as an enemy of Dracula. In Todd McFarlane's comic book Spawn, Neil Gaiman introduced Cagliostro to the series. In the comic book, Cagliostro was once a spawn of Hell and was bound to his duty to the daemon Malebolgia. However, he freed himself of the curse through alchemy and sorcery. Throughout the series, he teaches Spawn to do the same.

Cagliostro is a playable character in the popular Japanese mobile game Granblue Fantasy. Additionally, the name of the Count was used for the 1979 animated feature Lupin III: The Castle of Cagliostro, which was co-written and directed by the legendary animator Hayao Miyazaki. However, it is important to note that there is no real relation between the character in the film and the historical figure of Count Cagliostro.

Although the Roman Inquisition destroyed many of his works, a copy of his Rite of Egyptian Freemasonry still exists. He is also believed to have written an alchemical manuscript called The Most Holy Trinosophia, which he carried with him during his ill-fated journey to Rome. Today, modern-day Masons and historians are rediscovering his Masonic ideas and philosophies, and his importance in the evolution of Freemasonry is being re-examined.

Despite his reputation as a flamboyant conman and magician, Count Cagliostro held some surprisingly progressive views for his time, particularly regarding women's rights and social welfare. He firmly believed in the equality of men and women, a radical notion in the 18th century. This conviction led him to take several groundbreaking steps.

Traditionally, Freemasonry was an exclusively male domain. However, Cagliostro defied convention by establishing female-only lodges within his Egyptian Rite of Freemasonry. Notably, he admitted women to the "Lodge of Isis", even appointing his wife, Countess Lorenza “Seraphina” Feliciani, as its Grand Mistress. This was a bold statement for gender equality within a powerful fraternal organisation.

Cagliostro drew inspiration from ancient Egypt and justified his inclusion of women by citing the prominent role of female priestesses in ancient Egyptian mystery religions. He believed that reviving these ancient traditions necessitated including women in his modern order.

He also engaged in philanthropy (with questionable origins). Cagliostro's wealth, while often suspected to be ill-gotten through his magical exploits and financial schemes, was also used for social good. He founded and funded a network of maternity hospitals and orphanages across Europe, providing crucial care for vulnerable women and children.

It's important to note that Cagliostro remains a controversial figure. His extravagant lifestyle, association with occultism, and dubious financial dealings cast a shadow over his genuine efforts towards social reform. However, there's no denying his forward-thinking ideas on women's rights and his commitment to helping the less fortunate, making him a complex and intriguing character in 18th-century history.

Bibliography

Beckman, Jonathan. Story of the occultist Alessandro di Cagliostro. YouTube. Mar 21, 2020.

Evans, Henry Ridgely. “Cagliostro and His Egyptian Rite of Freemasonry.” Reprinted from New Age Magazine (1919). https://archive.org/embed/EvansHRCagliostroHisEgyptianRiteOfFreemasonry1919

Faulks, Philippa and L.D. Cooper, Robert. The Masonic Magician: The Life and Death of Count Cagliostro and his Egyptian Rite. London: Watkins Publishing, 2017.

Faulks, Philippa. “Count Cagliostro the Masonic Magician by Phillippa Faulks (Full Lecture)”. August 11, 2021. Educational Video, 42:32.

Lee, Philippa. “Cagliostro the Unknown Master.” The Square Magazine. February, 2021. https://www.thesquaremagazine.com/mag/article/202102cagliostro-the-unknown-master/.

McIlvenna, Una. “How a Scandal Over a Diamond Necklace Cost Marie Antoinette Her Head.” History. December 4, 2018. https://www.history.com/news/marie-antoinette-diamond-necklace-affair-french-revolution.

Stuff You Missed in History Class, “Cagliostro.” October, 2021. Podcast, 45:46.

Trowbridge, W.R.H. Cagliostro: The Splendour and Misery of a Master of Magic. London: Chapman and Hall Ltd., 1910.

Jean-Eugène Robert-Houdin, Memoirs of Robert-Houdin, (London: Chapman and Hall, Ltd, 1860), 234-235, https://archive.org/details/memoirsofroberth00roberich/page/234/mode/1up.

Henry Ridgely Evans, History of Conjuring and Magic, (Kenton: William W. Durbin, 1930), 79-80, https://archive.org/details/history-of-conjuring-and-magic-by-henry-ridgely-evans-z-lib.org/page/79/mode/1up.

Jean Hugard, John J. Crimmins Jr. and Glen Gravatt, Encyclopedia of Card Tricks, (New York: Dover Publications, Inc, 1974), 201-202, https://archive.org/details/encyclopediaofca00huga/page/201/mode/1up.

This is a Bizzare Magick version of the trick commonly known as Grandmother's Necklace or Cords of Phantasia, which was first published in Scot’s Discoverie of Witchcraft in 1584. Bob Farmer has also published a similar trick in Genii (Vol. 80 No. 3) called “Bring Me The Head of Reginald Scot”, which also uses a small skull and two leather laces.

David Saltman, “Houdini’s Adventures in Paris,” The Houdini File, October 23, 2014, http://www.houdinifile.com/2014/10/houdinis-adventures-in-paris.html.

W.R.H. Trowbridge, Cagliostro: The Splendour and Misery of a Master of Magic, (London: Chapman and Hall, Ltd, 1910), 193-194, https://archive.org/details/cagliostrosplend00trowuoft/page/193/mode/1up.

Considerable doubt about the existence of Althotas has been expressed by authors who specialise in occultism. Many believe this is just one in a long list of lies told by Cagliostro. However, the French writer Louis Figuier, author of L’alchimie et les alchimistes (Paris, 1854), stated that the Roman Inquisition collected substantial evidence that Althotas did, in fact, exist. See Encyclopedia.com for more information.

Mecca is the capital of Mecca Province, located in the Hejaz region of western Saudi Arabia. It is widely regarded as the holiest city in Islam. The Sherif, Sharif or Sharifah was the leader of the Sharifate of Mecca. They were traditionally responsible for the stewardship of the Islamic holy cities of Mecca and Medina and the surrounding Hejaz region. The term “Sharif” is an Arabic word that means “noble” or “highborn”. It is typically used to refer to the descendants of the Islamic prophet Muhammad’s grandson, al-Hassan ibn Ali.

Chris Bennett, “May 2018 AOM: Liber 420: Cannabis, Magickal Herbs and the Occult,” Graham Hancock, May 1, 2018, https://grahamhancock.com/bennettc1/.